Sascha Braunig in conversation with Matt Savitsky

Matt

It's recording.

Sascha

I'm scared.

Matt

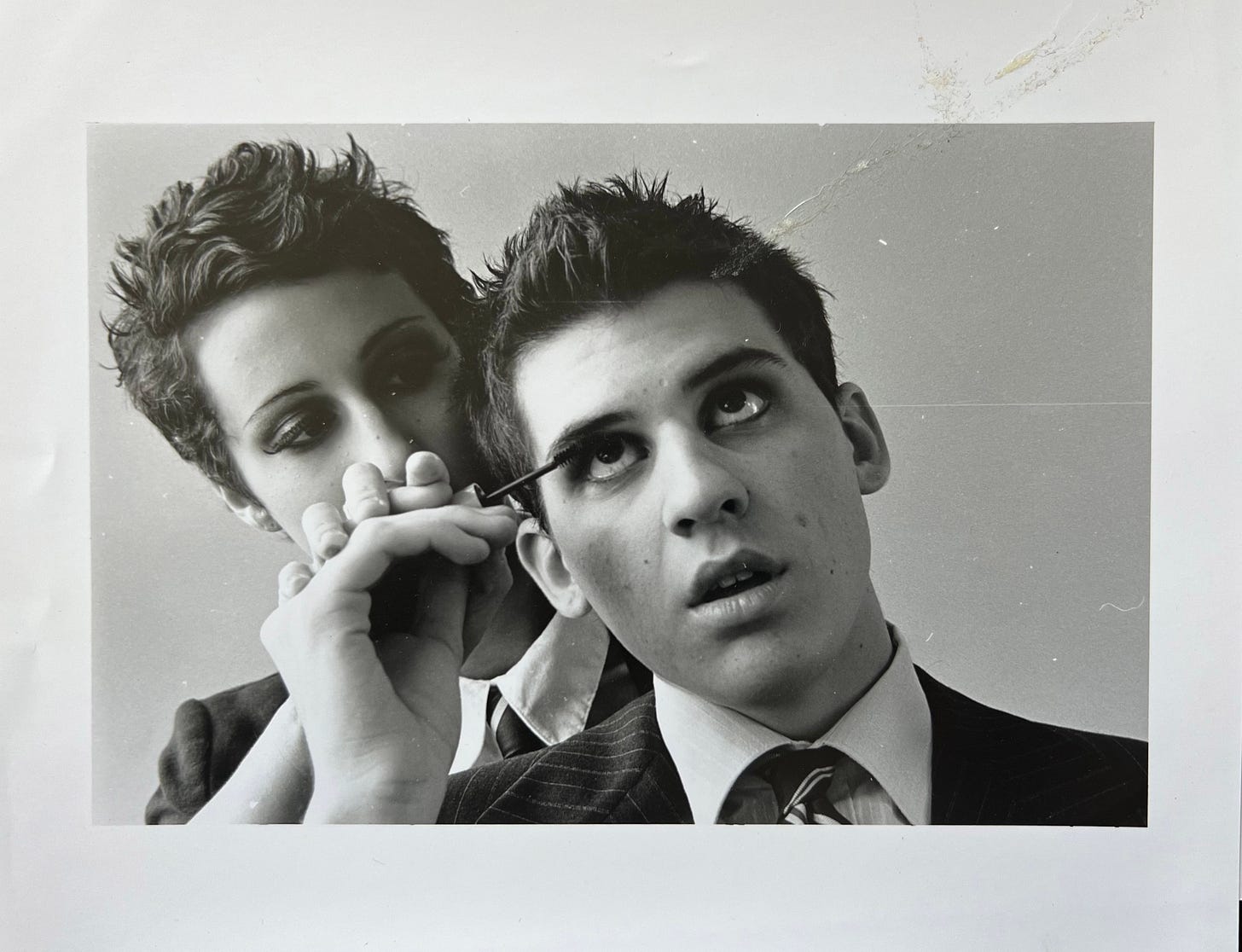

I feel nervous too. It brings up a lot to look back at all of those photos of us partying together.

Sascha

Maybe it was strange to look at those right before we spoke, because that's not who we are anymore. But maybe it’s the most vulnerable version of who we are.

Matt

In the pictures?

Sascha

Yeah. I invited you because I had the hope that you would make this a more personal conversation. I know that’s something you’re gifted at doing.

Matt

But I never know if you want to share personally, and I feel like a lot of interesting tension that I see in your work is about this - and the childhood cartoons have it too, which was blowing my mind - this internal conflict about wanting and needing to share, but then the discomfort that brings up for you.

Sascha

I mean, you should just be my therapist. It’s so true, I do want to share, I do want to expose myself through my work, but exposure also terrifies me. Making paintings is a way of exposing my thoughts and private self silently through objects that I send out into the world, so I don't have to do it directly. But when I was invited to do this interview, I thought it might be an interesting experiment to try to share more directly in a conversation - not in art objects.

Matt

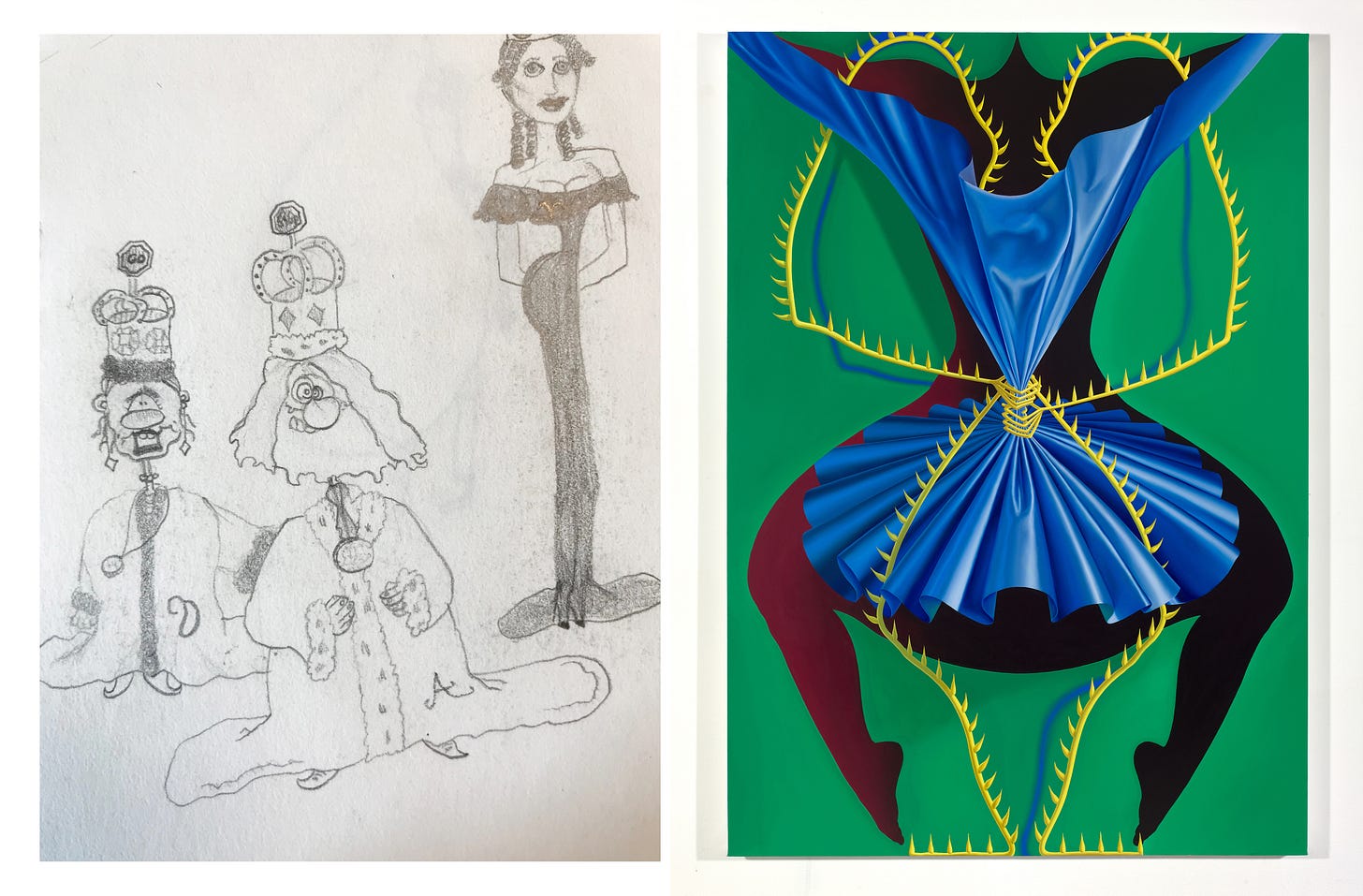

We were looking at your childhood drawings before this, and how they were really autobiographical, actually.

Sascha:

Yeah, with the character of my dad.

Matt

Yeah, so many of them were a unit of three. Your mother or father and then you. I love that drawing of the king and queen with the stop-and-go signs above their head. It's such an amazing translation of the good cop, bad cop dynamic. And you've defaced them. They're kind of made clownish and then you’ve exaggerated yourself, but in the opposite direction, where you're like, kind of a cinched waist beauty queen, who's towering over them.

Sascha

I wasn't thinking of myself as that Princess at all. But it's interesting to point out that it's a trio and that I was constantly depicting trios, it's true. As an only child.

Matt

I guess I focused in on that as a self portrait because you went to the trouble to pick out all of the drawings that had cinched waists. I want to hear you talk more about that artifact from those drawings, and how it's still so prevalent in the paintings you're doing now, which I believe are still self portraits in a way.

Sascha

Maybe they're portraits of a mental state of conflict. A conflict between anger, and a desire for something. That’s what my childhood cartoons are about too, because as a kid, I was really influenced by Mad Magazine and other “counterculture” comics. They were teaching the audience to be wise, to be cultural critics and skeptics, to not accept anything from mainstream culture as truth. But then they were also depicting women in really misogynistic ways. I think I really latched on to both of those things and unfortunately for my kid brain, equated them.

I processed that media through starting to make my own comics. Part of doing that was replicating the mockery of women's bodies, and making fun of some notion of mainstream femininity.

But part of me also revered that mocked femininity. Because I think those cartoonists I was copying from revered it and sexualized it too. Femininity was held up in these images as something desirable and sexy, but also ridiculous. I guess I'm still dealing with that.

Matt

But now you’re an adult. Whereas before you were in girlhood.

Sascha

Yeah, those drawings we were looking at were from when I was 10 or 11. I hadn't even gone through the part of my life where I transformed myself from an androgynous kid into a strictly conforming pre-woman. That shift, for me, was really sudden. I treated it really strictly like a project. The transformation from being a weird kid who dressed androgynously, flamboyantly even - dressing in the crazy colors of the early 90s - it felt like in order to survive socially, I had to quickly adapt, to change my entire wardrobe, the entire way that I looked in the span of six months to a year. Did that occur for you at all?

Matt

Well, don't worry about me.

(laughter)

But no, it's interesting, I’m looking at the drawing of you onstage as a stand up comedian. And the depiction is essentially that of an androgynous clown. Versus this other kind of hyper feminine, buxom woman that you were seeing in Mad Magazine?

Sascha

I think those were the two polarities, or binaries of femininity, that were fed to us. If you weren't one thing, then you had to be the other, maybe. So yeah, at the age of 12, I completely committed to being the femme version, and I think that still has ramifications. Depending on the day, I feel like I'm more or less “achieving” a coherent outer self.

Matt

What's interesting is the similarity between the comic on stage and the figures in your paintings, which are also in front of curtains, kind of spotlit, and almost addressing an audience.

Sascha

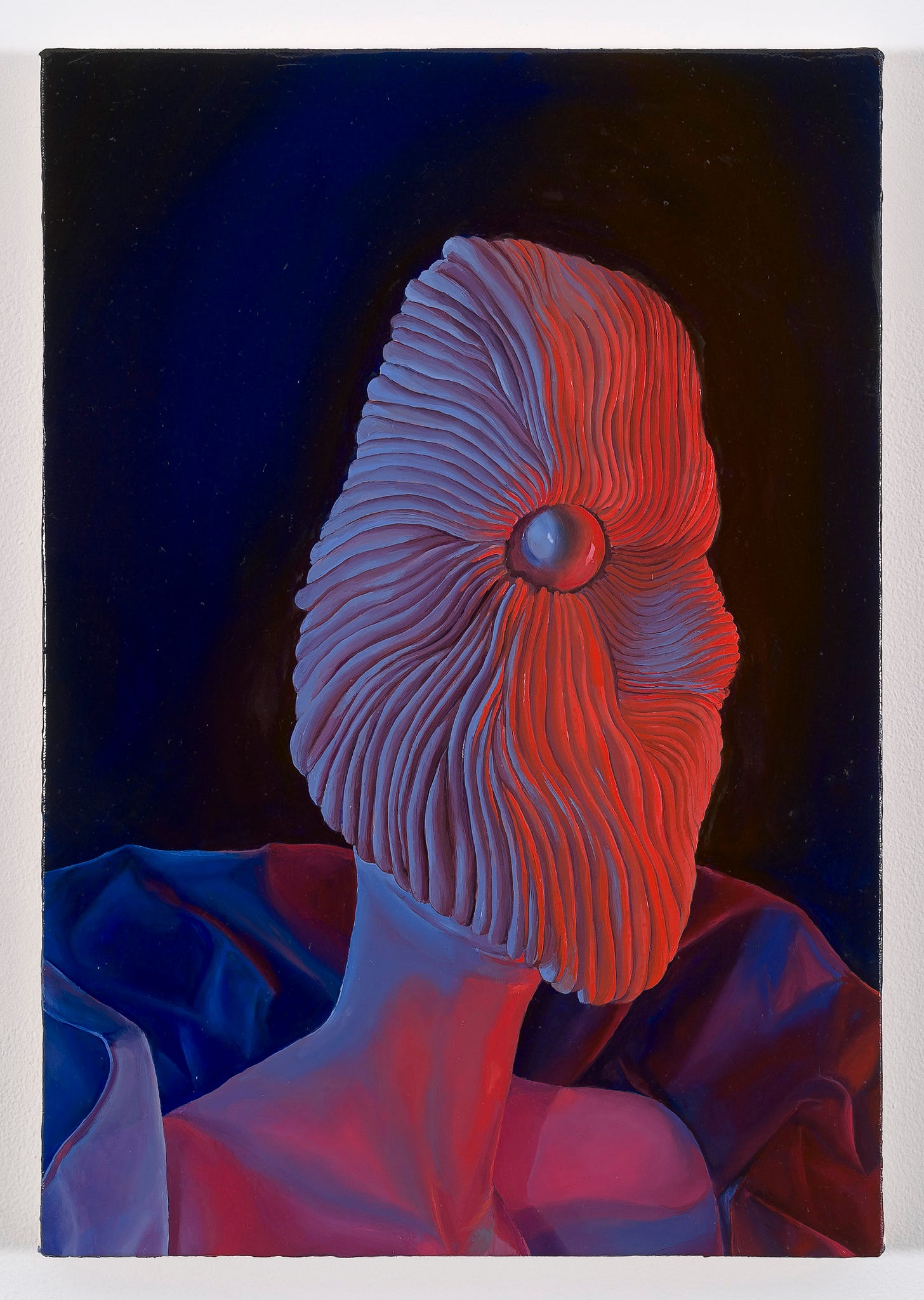

We had a studio visit where you were talking about the stagecraft of the paintings - the space of the paintings being like the front of a stage. I really think that's right. I’ve been thinking about how the painting surface is a threshold between an audience, and whatever's occurring on the stage. That threshold is an important feature of the work – I want the viewer to meet the surface and to participate in it in some way, even if it's just in terms of spectating. I want that participation to be almost physical. That the viewer could physically project themselves into the painting is important to me.

Matt

When there's an actor on stage, if they trip and fall or forget their line, it's so excruciatingly humiliating for the audience, actually.

Sascha

Because the illusion is broken.

Matt

Yeah. You're seeing someone fail at holding their own illusion, and the thing is exposed as an illusion through the mistake. And the mistake can kind of overpower and be the most memorable thing of the entire play.

Sascha

Well, that's where perfection and control come into the conversation because I want to avoid the audience experiencing that mistake. And that's why every element of the composition and execution has become so important to me. I render seamlessly so that the painting, when it’s finished, can elicit this perfect feeling that I'm looking for. For the viewer, and also for me.

Matt

Right.

Sascha

So my studio practice is all about controlling the object as I'm painting. Even though I'm not necessarily in control of it, but rather it's in control of me. I'm in thrall to it. That doesn't always feel good. That feels like domination actually, like the painting is dominating me during this painting process. But then, hopefully, at the end, when I'm looking at the finished thing, there's some kind of catharsis from that bondage of the process. I guess I'm setting up a situation of control just in order to feel released from it.

Matt

Where does the process happen for you? So much of the painting seems like production. Where are the feelings you’re describing coming up - in the act of painting?

Sascha

That's a good question. There is so much production; sketching, making a model, making a study, mocking up the painting to scale. I don't know.

Matt

Would you say the paintings are a more removed translation of the drawings?

Sascha

Yeah, they're more stage-managed. The drawings are straight from my mind, unadulterated. But by the time they're a painting, they've gone through this translation process where I’ve made a three dimensional model. I light it and paint from observation, to some extent. It’s funny, I'm reverse engineering, in a way - I know how I want it to look, and then the model exists as an aid so I can find moments of light and shadow that look graspable. That’s an important feature for the viewer’s experience, but it’s unrelated to the germ of the idea.

Matt

I’ve had this conversation with other painters, too. How the sketchbook is for you, right. Then the actual painting, which is the work people see, is this step of removal from an unpolished thing to something with a clear audience in mind. In my work I’ve struggled with that, especially being a trained painter. I’ve actually tried really hard -

Sascha

- to divest yourself?

Matt

Yeah. The closer I can get people to the formation of the idea is what I want people to see. I’ve burdened people at times, with too much. I can see that even reflected with how I am socially.

Sascha

I think that your practice mirrors the way you want to be in the world, which is open, and shifting. Not trying to create these moments of perfection in a perfect object. And I totally admire that. Even as I engage in the total opposite kind of practice. But the sketchbook, of course, is always the best. They can't take that away from you.

laughter

Matt

If I'm comparing us, which is where I started - your archive is clean, and mine feels like my mistakes are very much on display.

Sascha

That's cool, though. We're not seamless.

Matt

Yeah. I feel committed to that for various reasons.

This made me remember an experience. It was a moment of separation, actually - I think I was so used to seeing you as a part of me and indistinct from me. When we went to Berlin you really, really wanted to go to this museum, with all this northern Italian Renaissance art, and I just wanted to go drink. I couldn't understand why you wanted to go so much. But then being with you, and having you point out areas of paintings that you were blown away by or confused by or disturbed by - all these distortions of bodies that lived hundreds of years ago - I really saw you in that moment in a way that I haven't forgotten.

Sascha

We just hadn’t aligned yet. I also wanted to go drink (laughter) - after looking at the paintings. Since our first art history classes I've been extremely enamored of painting history, and the kind of time travel that is involved in being able to relate to a painting move that someone’s made 500 years ago. Feeling linked up with that, like you have a connection with that artist over time. And potentially how your painting could have the same life after you’re gone.

Matt

Your paintings now do have that quality of being real objects in real space. But, you know, they also defy gravity, they feel brittle, they feel imaginary. You were talking about longing for an earlier painting experience that was more faithful to a still-life object. I’m wondering if that is going to come back?

Sascha

I don't think you can go back. Those paintings from around 2010 were about a thing I was going through personally, which was figuring out how to face the world and face other people, and being terrified of it. The early paintings were about masking, porosity, and how ornamentation and pattern can function as armor, while also being camouflage allowing you to fit into your environment. Over time, I became more interested in a bodily experience for the viewer, rather than one that is located in the head. So, the paintings gradually scaled up and became the size of a body. And now I feel like there's some kind of narrative going on that I'm quite attached to, even if it's a psychological narrative.

Matt

Which is what?

Sascha

What is the narrative? I guess two figures engaged in conflict. In this threshold space we were just talking about. A narrative about gender training, where the cinched waist stands in for the cultural forces that train, shape and mold us. The other figure, the spiky or dashed figure is grasping that dress and trying to either restrain it or attain it. It's a narrative that's also somewhat indecipherable.

Matt

It sounds more like a dynamic to me. Does it feel narrative because there aren't other real people involved?

As you were talking about letting go of the decorated busts as your early subjects, I was thinking about how those paintings were made of lifecasts of you and your close friends. And how letting go of those tracks with the shifts in your life, how friend groups look really different now than in our 20’s. What I heard you say is that leaving New York made space for you to do this kind of self reflection, where your studio actually became peopled with other figures. Not that you're remaking your friend group, but that it gave you space to go back to your core.

Sascha

Yeah, that’s really how it felt when I first moved to Maine. I was pretty isolated here for the first few years. I have way more of a community now, but I have stripped away a lot. I don't teach anymore, I don't really do talks anymore. Everything is about getting to the studio and getting to the painting chair. So part of doing this conversation with you is an effort to be a little bit more open to talking about my work and admitting life into the studio a bit.

Sascha Braunig lives and works in Portland, Maine. She holds a BFA from Cooper Union and an MFA in painting from Yale University, and has been awarded residencies at MacDowell, Sharpe-Walentas Studio Program, and Surf Point. Recent solo exhibitions include Poseuses, François Ghebaly, Los Angeles (2023); Lay Figure, Oakville Galleries, Ontario (2022); Lay Figure, François Ghebaly and Magenta Plains, New York (2022); and Extra Spectral (with Bianca Beck), SPACE, Portland, Maine (2019). Past institutional solos include Bad Latch, Atlanta Contemporary (2017); Shivers, MOMA PS1 (2016); and Torsion, Kunsthall Stavanger, Norway (2015). In 2023, the second catalogue of her work was published jointly by Oakville Galleries and Triangle Books.

Matt Savitsky is a LA-based interdisciplinary artist whose often collaborative work combines performance, video, and sculptural installations. He received the 2022 Grant to Visual Artists Award from the Foundation of Contemporary Art in New York. He has had solo exhibitions at Cloaca Projects, San Francisco, CA (2019) and Shoot the Lobster, Los Angeles, CA (2017), among others. He has participated in group exhibitions at the Orange County Museum of Art, Santa Ana, CA (2019); The Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA (2018); and Torrance Art Museum, Torrance, CA (2016). His video works have been screened in the Migrating Forms Film Festival, New York, NY (2010); at Galeria Alternativa Once, Monterrey, Mexico (2014); and at Universidad del País Vasco Bilbao, Leioa, Spain (2014). Savitsky has debuted solo performances at Human Resources, LA (2023), the Orange County Museum of Art, Santa Ana, CA (2019); The Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA (2018); NADA, New York, NY (2017); and Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions, Los Angeles, CA (2016).

Savitsky has attended residencies hosted by Kembra Pfahler’s Incarnata Social Club, Reno, NV (2016) and by La Pocha Nostra at Highways, Los Angeles, CA (2016) and Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Tijuana, Mexico (2016). Savitsky was a member of The Family Room collective, an interdisciplinary group whose other members included Todd Moellenberg and Sylke Rene Meyer. They have created and shown work at Northridge Art Galleries, Los Angeles, CA (2019); California State University, Los Angeles, CA (2019); and Tiger Strikes Asteroid, Los Angeles, CA (2019).

He received a B.F.A. from The Cooper Union in 2005 and an M.F.A. from University of California, San Diego. He lectures on Film & Video and Photographic Practices at California State University, Fullerton.